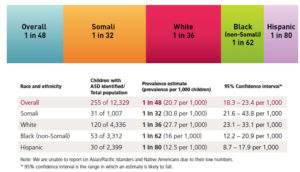

Though ASD is known to occur in children and adults from all backgrounds, there are glaring differences in diagnosis and treatment across racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups. In the United States, minority and lower-middle class children are diagnosed later and treated less effectively than wealthy Caucasians, leading to severe disparities in function between ASD children who are identified and treated well and those who are overlooked or misrepresented by doctors and educators.

Relative ASD diagnosis rates

Reasons for these differences in diagnosis and treatment include an array of related factors, perhaps most significantly a combination of skewed professional impression of the child in question and lack of parental recognition of ASD traits. More specifically, discrepancies between ASD diagnosis in minority children and diagnosis in Caucasian children are attributed to financial disadvantage, lack of education, and cultural or language barriers for the minority individuals involved.

For example, cultural differences and stereotypes may alter a parent or physician’s perspective on certain behaviors. On the professional side, a middle-class Caucasian child from a traditional household may be tested for ASD after failing to succeed in the classroom. A poor African American child displaying similar behaviors may be labeled as “disruptive” or “acting out.” On the parental side, there is significant evidence to show that minority parents are less likely to report autism-like behavior and may fail to provide the complete picture when they do note an issue. As a result, their children never receive the therapy and accommodations that could lead to success.

Solutions for this significant intersectional issue are currently being researched, as the implications of equal opportunity for ASD individuals are only positive and have the potential to impact society as a whole. The neurodiversity movement’s most powerful tool in this situation is, by far, education. Because minority cultures have a variety of beliefs regarding health and disability, their perspectives on brain differences in children are often significantly different than the criteria outlined in the DSM. Furthermore, because the DSM is the official “rulebook” for ASD diagnosis, the acquisition of help and resources depends on parents recognizing relevant symptoms and seeking professional attention.

This is not to say that minority cultures should alter or contradict their values. In fact, studies have reported higher degrees of acceptance and empathy in Latino cultures as well as other minority groups. This is largely positive. Instead of being encouraged to change, parents should be educated on the American system in order to make the most informed decision possible to help their child succeed, and should have uninhibited access to the resources provided.

The NBCI is an activist organization that has partnered with Autism Speaks in an effort to spread awareness of ASD in the African American community.

In order for there to be a cohesive shift in the way American culture educates, diagnoses, and treats ASD individuals and their families, the medical and educational fields need to work alongside citizens to understand and tackle the challenges associated with ASD and other brain differences. Adoption of a neurodiversity perspective in contrast to a more objective desire to “fix” ASD individuals is perhaps the simplest but most important change to be made in this area.

Speak Your Mind